In 1939, Raymond Chandler published The Big Sleep, a hard-boiled crime novel adapted into the 1946 film by the same name. Both the novel and the film became famous for their gripping (but at times frustrating) plots, which included multiple loose ends. Today, we’re challenged to match the crime-solving prowess of fictional private eye Philip Marlowe with our own ability to gauge the health of the world’s economy and the fate of financial markets. Is the global expansion headed for the “Big Sleep?” It will be a difficult case to solve, requiring deductive and intuitive detective work.

What do the data tell us?

The logical place to start searching for clues about the global economy would be in the economic data. The trouble with this approach is that, thanks to the protracted U.S. government shutdown, most relevant U.S. data has been coming in at least one month late. And much of the data we are receiving has been warped by the shutdown itself, even if it’s difficult to tell by how much. Consumer spending and business activity were undoubtedly hit by the absence of government checks in December and January. Some of that activity was likely recouped in February and March, and will continue to bounce back in the second quarter, but we won’t know for quite some time how the first half of 2019 has shaped up.

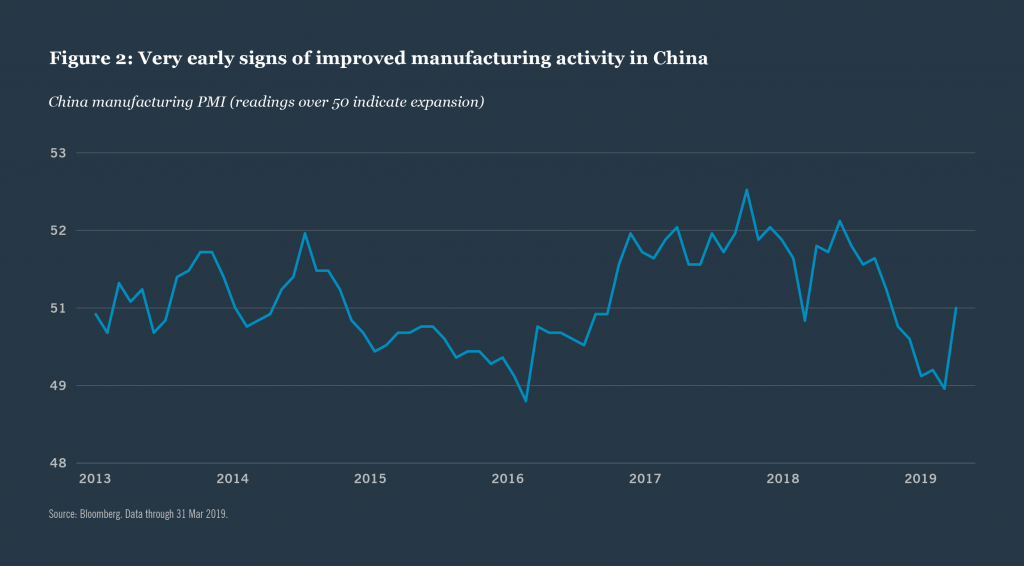

While the data is at least arriving on time in China, it’s painting a picture of slowing growth rather than recovery. China’s growth slowed by more than expected in 2018, and by all accounts that slowdown has persisted into this year. Factory output has fallen, and consumer spending and investment are merely stable, despite considerable efforts by the Chinese government to provide stimulus. We are seeing some signs of renewed growth in the Chinese economy, such as a recent pickup in manufacturing (Figure 2), but overall growth has only just begun to recover, despite months of deregulatory and tax-reducing policies.

The situation is similar in the Eurozone, where some evidence suggests the economy has bottomed and begun to recover, while other data suggest the worst is not yet over. Industrial production surged in January, but manufacturing sentiment has continued to worsen throughout the quarter, culminating with a shockingly poor reading in March. Europe may also continue to be plagued by the risk of a messy Brexit after the U.K. was granted an extension of its March 29 deadline to leave the European Union. And the continent remains susceptible to a breakdown of U.S./China trade talks, given the importance of trade to growth.

As they have for much of the past decade, U.S. consumers remain the lynchpin of any potential bounce in global growth. Retail sales growth has begun to bounce back from a horrible December, and we see more reasons for cheer in so-called “soft” data like consumer confidence. Consumer expectations for the economy have historically been correlated to spending behavior, so the recent recovery in these surveys may indicate that consumption growth can climb further (Figure 3)

The upshot of our analysis of recent global economic data is this: It’s going to be a tougher climb for growth in 2019, but it will be a climb higher nonetheless. The world is likely to avoid a recession or even a severe slowdown, even as GDP climbs by less than it did last year. However, given the delay in U.S. data releases and the doubts over the efficacy of China’s ongoing stimulus measures, we see an unusual amount of uncertainty around our benign outlook. And so we must look elsewhere for corroboration.

What does the markets’ behavior tell us?

Having scoured the global landscape for clues in the economic data, we now move to another aspect of our detective story: divining meaning from the impressive first quarter rallies in both global stocks and bonds. Financial markets sounded a far louder alarm during the December panic than hard economic data actually did, and likewise exhibited a more convincing recovery in the first quarter. While most risk asset prices have yet to recover to their 2018 highs, volatility has plummeted, and recession risks are no longer priced into markets. How did this shift happen so quickly?

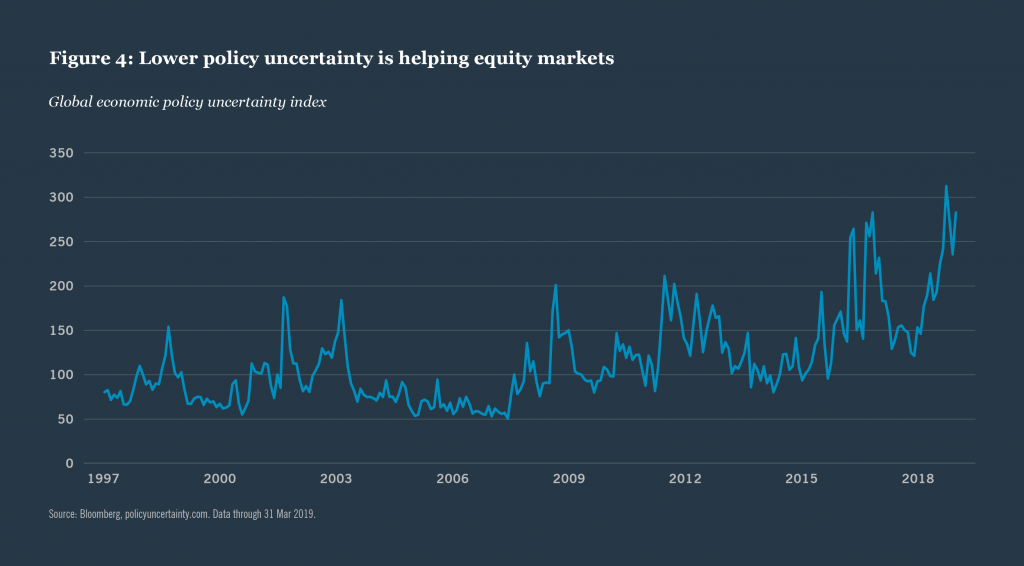

The growth scare and global equity market correction in late 2018 was driven in part by a spike in both the number and the severity of global policy risks. Tighter global monetary policy, escalating trade tensions and Brexit uncertainty all presented credible threats to the investment outlook. To varying extents, those risks have abated in the first quarter of 2019. Brexit and the U.S./China trade negotiations have yet to be resolved, but it seems likely (for the moment at least) that we will avoid the worst case outcomes. As a result, investors have collectively become more comfortable owning equities and corporate bonds. History and our experience suggest these assets tend to be attractive options when policy risks fall from elevated levels.1

Historically, the only refuge for investors seeking positive returns during a period of acute event risk or recession was long-duration, high quality bonds. On the equity side, while few stocks could eke out positive returns in a bear market, defensive sectors like consumer staples and health care would likely beat technology and financials. Moreover, established commercial real estate and defensive real assets like farmland may mitigate against the forces of the public markets.

At the same time, central banks’ newly dovish rhetoric and policy choices, about which we’ll have more to say in a moment, have allowed interest rates to remain low and kept equity markets elevated by limiting the risk that rising interest rates and tighter credit conditions will prematurely end the global expansion. The net result has been a “free lunch” of sorts for global investors. Returns on both global bonds and global stocks have comfortably beaten cash, reversing the pain of last year when the opposite occurred.1