But when you look back at historical U.S. inflation episodes like the double-digit increases seen in the 1970s, they started as a tight economy received an initial shock (e.g., a spike in oil prices), followed by a series of policy decisions (wage and price controls, a reluctance to hike interest rates in the face of spiraling prices) that exacerbated the situation.

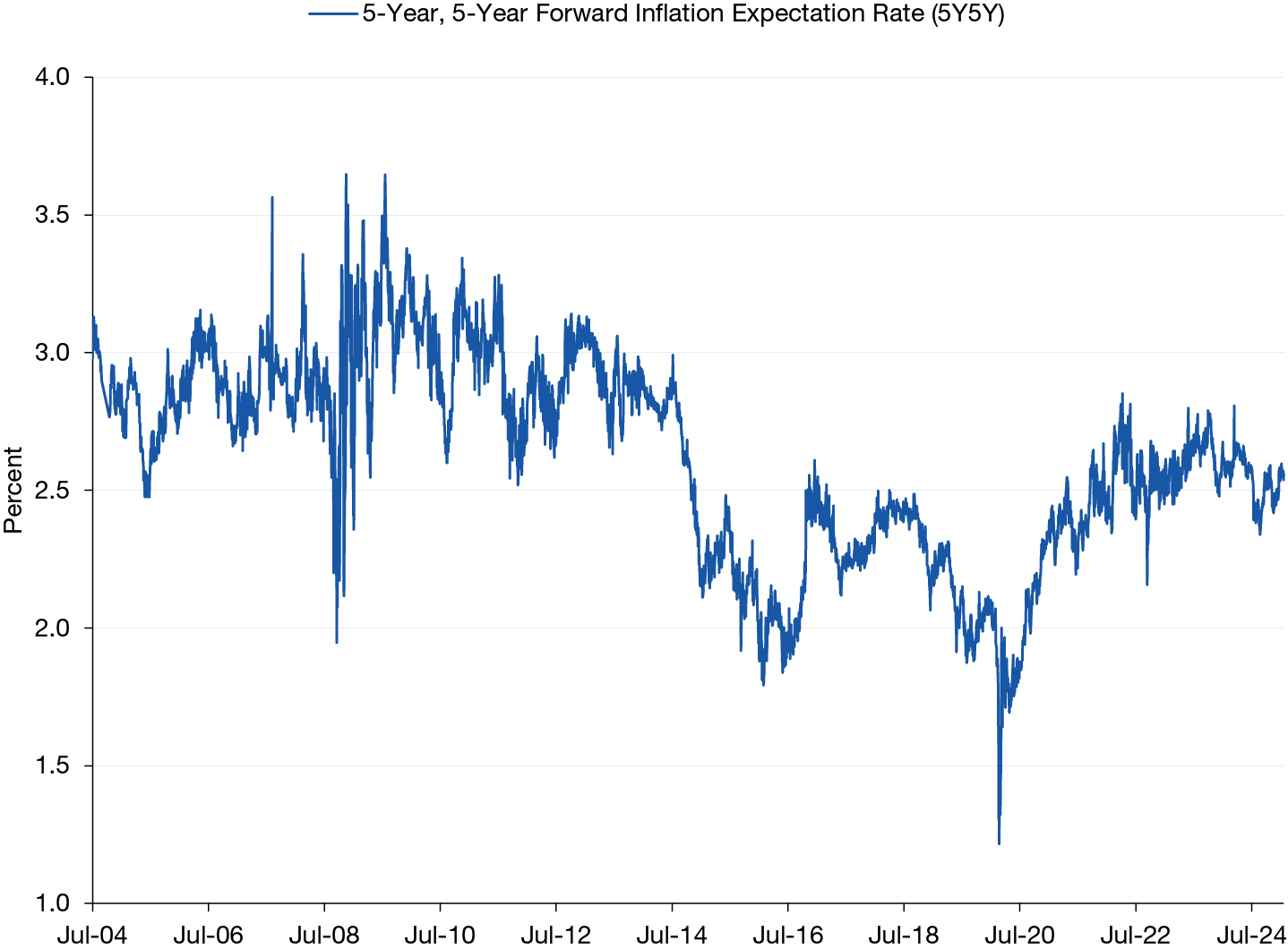

Fast forward to early 2025. The recent tariff announcements have come at a time when consumers and businesses have been sensitized to price increases after the long stretch of low inflation that preceded the COVID episode (in the 10 years before the onset of the pandemic in early 2020, monthly readings of the year-over-year headline U.S. consumer price index [CPI] ranged from -0.1% to 3.9%). Nonetheless, as Figure 1 shows, the big inflation shock of 2021-22 did not result in expectations becoming de-anchored.

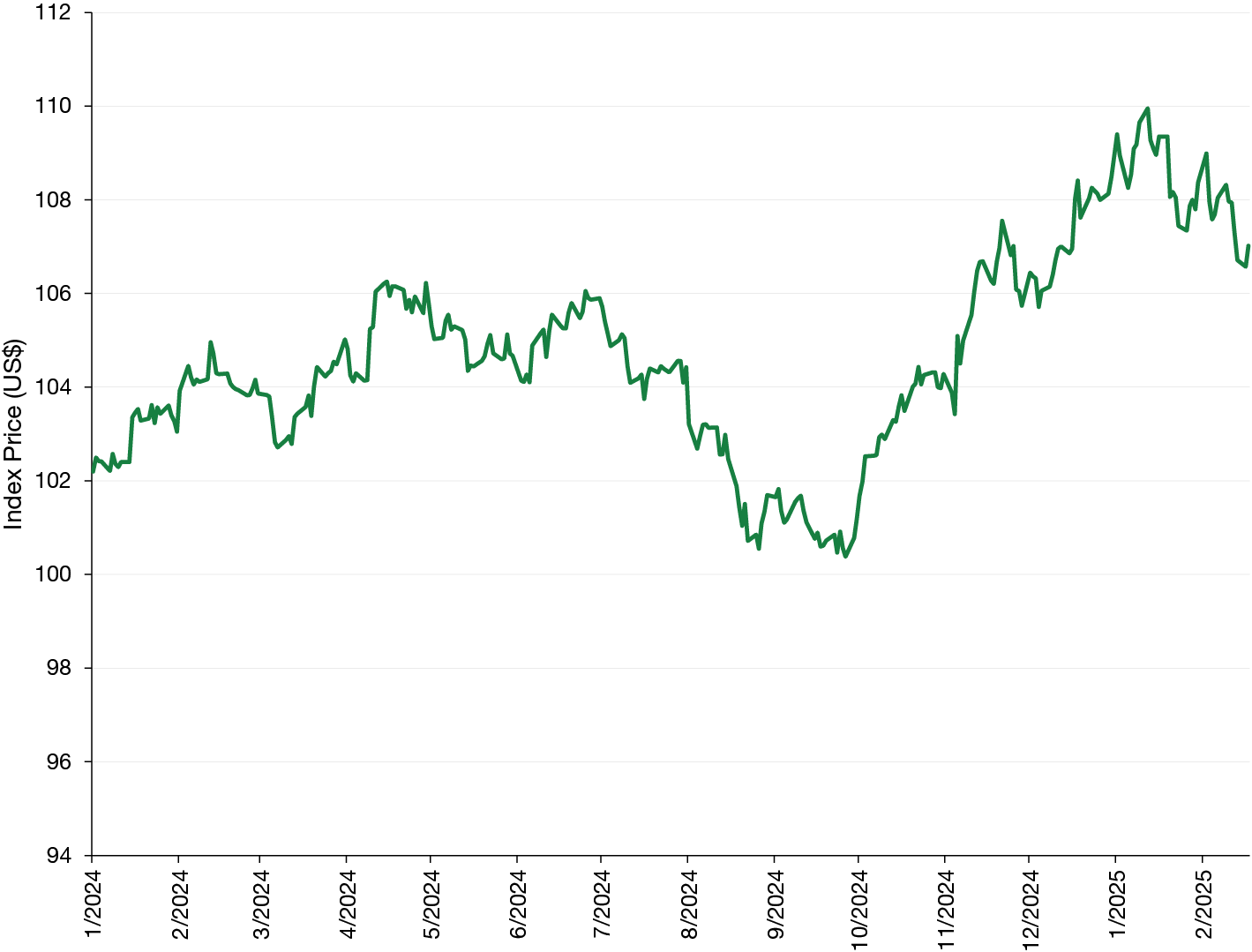

However, the waters have been muddied by a much higher-than-expected 0.5% increase in the headline CPI for January 2025, as reported by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on February 12. A fresh uptick in prices, coming amid the expected imposition of double-digit tariffs across a range of nations and product categories, may give businesses a greater propensity to raise prices if they expect inflation to trend higher in coming months. Another jump in prices, coming as the memories of the 2021-22 episode are still fresh, may translate into a larger increase in inflation expectations than would be expected based on the last one in isolation. In other words, expectations for future prices risk getting destabilized by repeated shocks after many years of relative calm. Of course, the situation remains fluid, and the amounts of, and timetables for, proposed tariffs are subject to change.

3. How long does it take for tariffs to influence prices?

The most recent evidence (based on observations in 2019 after the implementation of tariffs in the first Trump administration) shows that tariffs are fully passed through into selling prices and/or margins of importing companies, either to consumers in the form of higher selling prices or coming out of importers’ margins. The full effect is not felt immediately; there is typically a 12 to 24-month lag.

One other thing to note is that while the stated intent of tariffs is to create an economic penalty on overseas goods producers, the brunt of the levies is borne by (1) U.S.-based firms who might absorb it into lower margins, and (2) by consumers, in the form of higher selling prices for goods.

4. Any impact on prices of domestically produced goods?

Tariffs directly affect the price of imported goods, but there also is solid evidence that there is an umbrella effect, in which domestic competitors for those imported goods also raise their prices.1 That would seem to be a rational response, especially if those domestic producers are capacity constrained in the short run. Producers of substitute goods (from a similar but not directly comparable category) also tend to raise prices.

There is also another potential effect on so-called complementary goods—those typically sold with the tariffed items. A 2020 study2 provides an example: In the last round of tariffs, duties were assessed on Chinese-made washing machines. The domestic selling price of washers increased directly (around 8%) as a result. Clothes dryers were not tariffed, but since washers and dryers are complementary goods (people tend to buy both at the same time), the price of dryers also increased by 8%, even though they were not subject to tariffs.

5. Would a stronger U.S. dollar offset the effects of tariffs?

Imported goods might be made more expensive by being tariffed, but that impact could be offset by movements in the currency, and recent studies suggest that something between 20% to 50% of the effect of the tariff is offset by a stronger dollar, as strength in the U.S. currency makes imported goods cheaper than they otherwise would be.3