The 3% Yield That Really Matters

- We see higher short-term U.S. rates having a profound impact: Investors can now earn returns in excess of inflation while taking on much less risk.

- The U.S. 10-year Treasury yield hit a four-year high of 3%. U.S. stocks slid despite strong earnings reports, but recovered later in the week.

- We expect a solid U.S. employment report this week. The Federal Reserve is expected to deliver an upbeat message on the economy.

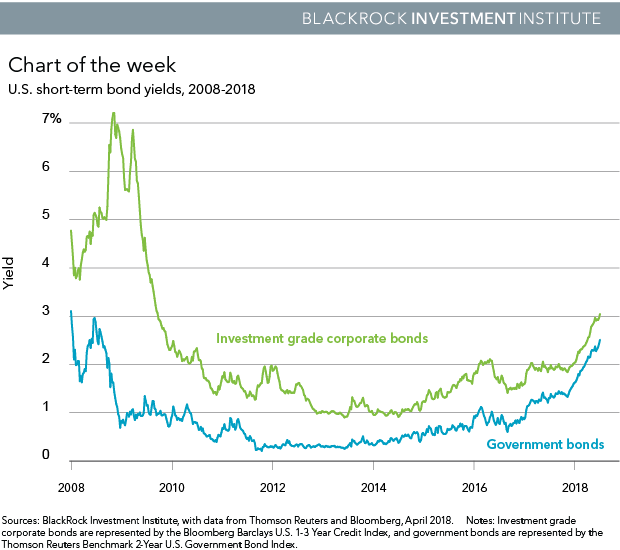

The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield touched 3% last week for the first time in more than four years – inciting much hand-wringing. Yet this overshadowed a similar milestone that we believe is of far greater significance to investors: Yields on short-term U.S. investment grade (IG) corporate bonds also hit 3% — an eight-year high.

Rock-bottom short-term interest rates over the past decade have driven income-hungry investors to riskier assets in search of higher yields. The chart above shows that yields on short-term IG corporate bonds have mostly languished below 2% since 2010 while two-year Treasury yields have hobbled below 1%. Yields on both have increased this year, with the corporate bond yield breaking above 3% and Treasury yield rising to just shy of 2.5%. Investors can earn positive after-inflation returns from these bonds for the first time since the global financial crisis. To be sure, rates are much lower in developed markets outside the U.S. Yet greater competition for capital from U.S. shorter-duration bonds has implications across asset classes.

“Safe” income makes a comeback

Rising confidence in the economy — and in the Federal Reserve’s resolve to press ahead on its normalization path — has helped drive up yields in the U.S. fixed income market, especially on the front end. One implication: “safe income” is back. Investors no longer need to take on as much risk to generate enough return to preserve purchasing power. A lack of lower-risk income sources since the financial crisis forced investors toward riskier assets, raising the demand for these assets amid relatively fixed supply. The result: higher prices for riskier assets like equities and tighter spreads for high yield and emerging market (EM) bonds. The increase in wealth and accommodative financial conditions stimulated spending and investment.

What happens as this process kicks into reverse amid rising rates? With the rise in short-term yields, we see assets closest to Treasuries repricing first as the competition for capital heats up. Rising rates, increased economic uncertainty and the return of market volatility have driven the spreads on other perceived “safe” short-dated assets, such as IG credit, wider. This has made such assets more attractive. We also see the yield curve steepening: Rising Treasury issuance and less buying from the Federal Reserve should lead to higher long-term yields. Firming inflationary expectations could add to these curve-steepening pressures.

Rising rates have been a key driver in the recent repricing of risk assets and bouts of volatility, but there are other factors at play. The sustained and steady economic expansion is supporting strong corporate earnings growth globally, underpinning our preference for equities. We expect rates to rise, but plentiful global savings to help limit the extent. This should remain a favorable environment for risk taking, we believe. Yet more competitive returns from “safe” assets imply muted returns on risk assets. We see future returns driven primarily by income in fixed income and earnings growth in equities, rather than by a rerating spurred by a decline in rates and risk.